The following is an amalgamation of versions of the Eros and Psykhe myth. It combines details from various authors whose including Thomas Bulfinch, Mary Pope Osborne, Edith Hamilton, Nancy Hathway, Michael Grant & John Hazel and the Roman poet Apuleius.

Eros and Psykhe[]

The story of Eros and Psykhe is one of the most famous myths, many authors have told it each adding certain details such as the name of Venus' (Aphrodite) handmaidens yet excluding other parts such as Psykhe's pregnancy. This version of the story combines details of many authors.

Eros and Psykhe "In a certain city there lived a king and with three notably beautiful daughters. The two elder ones were very attractive, yet praise appropriate to humans was thought sufficient for their fame. But the beauty of the youngest girl Psykhe, was so special and distinguished that our poverty of human language could not describe or even adequately praise it. In consequence, many of her fellow-citizens and hordes of foreigners, on hearing the report of this matchless prodigy, gathered in ecstatic crowds. They were dumbstruck with admiration at her peerless beauty. They would press their hands to their lips with the forefinger resting on the upright thumb, and revere her with devoted worship as if she were none other than Aphrodite herself. Rumor had already spread through the nearest cities and bordering territories that the Goddess who was sprung from the dark-blue depths of the sea and was nurtured by the foam from the frothing waves was now bestowing the favor of her divinity among random gatherings of common folk; or at any rate, that the earth rather than the sea was newly impregnated by heavenly seed, and had sprouted forth a second Aphrodite invested with the bloom of virginity. This belief grew every day beyond measure. The story now became widespread; it swept through the neighboring islands, through tracts of the mainland and numerous provinces. Many made long overland journeys and travelled over the deepest courses of the sea as they flocked to set eyes on this famed cynosure of their age. No one took ship for Paphos, Knidos, or even Cythera to catch sight of the goddess Aphrodite. Sacrifices in those places were postponed, shrines grew unsightly, couches become threadbare, rites went unperformed; the statues were not garlanded, and the altars were bare and grimy with cold ashes. It was the girl who was entreated in prayer. People gazed on that girl's human countenance when appeasing the divine will of the mighty goddess. When the maiden emerged in the mornings, they sought from her the favor of the absent Aphrodite with sacrificial victims and sacred feasts. The people crowded round her with wreaths and flowers to address their prayers, as she made her way through the streets. Since divine honors were being diverted in this excessive way to the worship of a mortal girl, the anger of the true Aphrodite was fiercely kindled. She could not control her irritation. She tossed her head, let out a deep growl, and spoke in soliloquy: ‘Here am I, the ancient mother of the universe, the founding creator of the elements, the goddess that tends the entire world, compelled to share the glory of my majesty with a mortal maiden, so that my name which has its niche in heaven is degraded by the foulness of the earth below! Am I then to share with another the supplications to my divine power, am I to endure vague adoration by proxy, allowing a mortal girl to strut around posing as my double? What a waste of effort it was for the shepherd whose justice and honesty won the approval of great Zeus to reckon my matchless beauty superior to that of those great goddesses! But this girl, whoever she is, is not going to enjoy appropriating the honors that are mine; I shall soon ensure that she rues the beauty which is not hers by rights!’

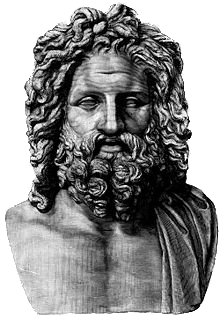

She at once summoned her son Eros, that winged, most indiscreet youth, whose own bad habits show his disregard for public morality. He goes rampaging through people's houses at night armed with his torch and arrows, undermining the marriages of all. He gets away scot-free with this disgraceful behavior, and nothing that he does is worthwhile. His own nature made him excessively wanton, but he was further roused by his mother's words. She took him along to that city, and showed him Psykhe in the flesh (that was the girl's name). She told him the whole story of their rivalry in beauty, and grumbling and growling with displeasure added: ‘I beg you by the bond of a mother's affection, by the sweet wounds which your darts inflict and the honeyed blisters left by this torch of yours: ensure that your mother gets her full revenge, and punish harshly this girl's arrogant beauty. Be willing to perform this single service which will compensate for all that has gone before. See that the girl is seized with consuming passion for the lowest possible specimen of humanity, for one who as the victim of Tykhe (good fortune) has lost status, inheritance and security, a man so disreputable that nowhere in the world can he find an equal in wretchedness.’

With these words she kissed her son long and hungrily with parted lips. Then she made for the nearest shore lapped by the waves . . . Meanwhile, Psykhe for all her striking beauty gained no reward for her ravishing looks. She was the object of all eyes, and her praise was on everyone's lips, but no king or prince or even commoner courted her to seek her hand. All admired her godlike appearance, but the admiration was such as is accorded to an exquisitely carved statue. For some time now her two elder sisters had been betrothed to royal suitors and had contracted splendid marriages, though their more modest beauty had won no widespread acclaim. But Psykhe remained at home unattended, lamenting her isolated loneliness. Sick in body and wounded at heart, she loathed her beauty which the whole world admired. For this reason the father of that ill-starred girl was a picture of misery, for he suspected that the gods were hostile, and he feared their anger. He sought the advice of the most ancient oracle of the Milesian God Apollo, and with prayers and sacrificial victims begged from that mighty deity a marriage and a husband for that slighted maiden. Apollo, an Ionian Greek, framed his response in Latin to accommodate the author of this Milesian tale: ‘Adorn this girl, O king, for wedlock dread, and set her on a lofty mountain-rock. Renounce all hope that one of mortal stock can be your son-in-law, for she shall wed a fierce, barbaric, snake-like monster. He, flitting on wings aloft, makes all things smart, plaguing each moving thing with torch and dart. Why, Zeus himself must fearful be. The other gods for him their terror show, and rivers shudder, and the dark realms below.’

The king had formerly enjoyed a happy life, but on hearing this venerable prophecy he returned him reluctant and mournful. He unfolded to his wife the injunctions of that ominous oracle, and grief, tears and lamentation prevailed for several days. But now the grim fulfillment of the dread oracle loomed over them. Now they laid out the trapping for the marriage of that ill-starred girl with death; now the flames of the nuptial torch flickered dimly beneath the sooty ashes, the high note of the wedding-lute sank into the plaintive Lydian mode, and the joyous marriage-hymn tailed away into mournful wailing. That bride-to-be dried her tears on her very bridal-veil. Lamentation for the harsh fate of that anguished household spread throughout the city, and a cessation of business was announced which reflected the public grief.

But the warnings of heaven were to be obeyed, and unhappy Psykhe's presence was demanded for her appointed punishment. So amidst intense grief the ritual of that marriage with death was solemnized, and the entire populace escorted her living corpse as Psykhe tearfully attended not her marriage but her funeral. But when her sad parents, prostrated by their monstrous misfortune, drew back from the performance of their monstrous task, their daughter herself admonished them with these words: ‘Why do you rack you sad old age with protracted weeping? Or why do you weary your life's breath, which is dearer to me than to yourselves, with repeated lamentations? Why do you disfigure those features, which I adore, with ineffectual tears? Why do you grieve my eyes by torturing your own? Why do you tear at your grey locks? Why do you beat those breasts so sacred to me? What fine rewards my peerless beauty will bring you! All too late you experience the mortal wounds inflicted by impious envy. That grief, those tears, that lamentations for me as one already lost should have been awakened when nations and communities brought me fame with divine honors, when with one voice they greeted me as the new Aphrodite. Only now do I realize and see that my one undoing has been the title of Aphrodite bestowed on me. Escort me and set me on the rock to which fate has consigned me. I hasten to behold this noble husband of mine. Why should I postpone or shrink from the arrival of the person born for the destruction of the whole world?’

After this utterance the maiden fell silent, and with resolute step she now attached herself to the escorting procession of citizens. They made their way to the appointed rock set on a lofty mountain, and when they had installed the girl on its peak, they all abandoned her there. They left behind the marriage-torches which had lighted their way but were now doused with their tears, and with bent heads made their way homeward. The girl's unhappy parents, worn out by this signal calamity, enclosed themselves in the gloom of their shuttered house, and surrendered themselves to a life of perpetual darkness.

But as Psykhe wept in fear and trembling on that rocky eminence, Zephyrus' (the West Wind's) kindly breeze with its soft stirring wafted the hem of her dress this way and that, and made its folds billow out. He gradually drew her aloft, and with tranquil breath bore her slowly downward. She glided down in the bosom of the flower-decked turf in the valley below. In that soft and grassy arbor Psykhe reclined gratefully on the couch of the dew-laden turf. The great upheaval oppressing her mind had subsided, and she enjoyed pleasant repose. After sleeping long enough to feel refreshed, she got up with carefree heart. Before her eyes was a grove planed with towering, spreading trees, and a rill glistening with glassy waters. At the center of the grove and close to the gliding stream was a royal palace, the work not of human hands but of divine craftsmanship. You would know as soon as you entered that you were viewing the birth and attractive retreat of some God. The high ceiling, artistically paneled with citron-wood and ivory, was supported on golden columns. The entire walls were worked in silver in relief; beasts and wild cattle met the gaze of those who entered there. The one who shaped all this silver into animal-forms was certainly a genius, or rather he must have been a demigod or even a god. The floors too extended with different pictures formed by mosaics of precious stones; twice blessed indeed, and more than twice blessed are those whose feet walk on gems and jewels! The other areas of the dwelling too, in all its length and breadth, were incalculably costly. All the walls shimmered with their native gleam of solid gold, so that if the sun refused to shine, the house created its own daylight. The rooms, the colonnade, the very doors also shone brilliantly. The other riches likewise reflected the splendor of the mansion. You would be justified in thinking that this was a heavenly palace fashioned for mighty Zeus when he was engaged in dealings with men.

Psykhe, enticed by the charming appearance of these surroundings, drew nearer, and as her assurance grew she crossed the threshold. Delight at the surpassing beauty of the scene encouraged her to examine every detail. Her eyes lit upon store-rooms built high on the other side of the house; they were crammed with abundance of treasures. Nothing imaginable was missing, and what was especially startling, apart from the breath-taking abundance of such riches, was the fact that this treasure-house had no protection whatever by way of chain or bar or guard.

As she gazed on all this with the greatest rapture, a disembodied voice addressed her: ‘Why, may lady, do you gaze open-mouthed at this parade of wealth? All these things are yours. So retire to your room, relieve your weariness on your bed, and take a bath at your leisure. The voices you hear are those of your handmaidens, and we will diligently attend to your needs. Once you have completed your toilet a royal feast will at once be laid before you.’ Psykhe felt a blessed assurance being bestowed upon herby heaven's provision. She heeded the suggestions of the disembodied voice, and after taking a nap and then a bath to dispel her fatigue, she at once noted a semicircular couch and table close at hand. The dishes laid for dinner gave her to understand that all was set for her refreshment, so she gladly reclined there. Immediately wine was delicious as nectar and various plates of food were placed before her, brought not by human hands but unsupported on a gust of wind. She could see no living soul, and merely heard words emerging from thin air: her serving-maids were merely voices. When she had enjoyed the rich feast, a singer entered and performed unseen, while another musician strummed a lyre which was likewise invisible. Then the harmonious voices of a tuneful choir struck her ears, so that it was clear that a choral group was in attendance, though no person could be seen.

The pleasant entertainment came to an end, and the advent of darkness induced Psyche to retire to bed. When the night was well advanced, a genial sound met her ears. Since the was utterly alone, she trembled and shuddered in her fear for her virginity, and she dreaded the unknown presence more than any other menace. But now her unknown bridegroom arrived and climbed into the bed. He made Psyche his wife, and swiftly departed before dawn broke. At once the voices in attendance at her bed-chamber tended the new bride's violated virginity. These visits continued over a long period and this new life in the course of nature became delightful to Psyche as she grew accustomed to it. Hearing that unidentified voice consoled her loneliness. Meanwhile, her parents were aging in unceasing grief and melancholy. As the news spread wider, her elder sisters learnt the whole story. In their sadness and grief they vied with each other in hastily leaving home and making straight for their parents, to see them and discuss the matter with them.

That night Psyche's husband (he was invisible to her, but she could touch and hear him) said to her: ‘Sweetest Psyche, fond wife that you are, Tyche, grows more savage, and threatens you with mortal danger. I charge you: show greater circumspection. Your sisters are worried at the rumor that you are dead, and presently they will come to this rock to search for traces of you. Should you chance to hear their cries of grief, you are not to respond, or even to set eyes on them. Otherwise you will cause me the most painful affliction, and bring utter destruction on yourself.’

Psyche consented and promised to follow her husband's guidance. But when he had vanished in company with the darkness, the poor girl spent the whole day crying and beating her breast. She kept repeating that now all was up with her, for here she was confined and enclosed in that blessed prison, bereft of conversation with human beings for company, unable even to offer consoling relief to her sisters as they grieved for her, and not allowed even to catch a glimpse of them. No ablutions, food, or other relaxation made her feel better, and she retired to sleep in floods of tears.

At that moment her husband came to bed somewhat earlier than usual. She was still weeping, and as he embraced her, he remonstrated with her: ‘Is this how the promise you made me has turned out, Psyche, my dear? What is your husband to expect or to hope from you? You never stop torturing yourself night and day, even when we embrace each other as husband and wife. Very well, have it your own way, follow your own hell-bound inclination. But when you begin to repent at leisure, remember the sober warning which I gave you.’

Then Psyche with prayers and threats of her impending death forced her husband to yield to her longing to see her sisters, to relieve their grief, and he also allowed her to present them with whatever pieces of gold or jewelry she chose. But he kept deterring her with repeated warnings from being ever induced by the baleful prompting of her sisters to discover her husband's appearance. She must not through sacrilegious curiosity tumble headlong from the lofty height of her happy fortune, and forfeit thereafter his embrace. She thanked her husband, and with spirits soaring she said: ‘But I would rather die a hundred times than forgo the supreme joy of my marriage with you. For I love and cherish you passionately, whoever you are, as much as my own life, and I value you higher than Eros himself. But one further concession I beg for my prayers: bid your servant Zephyrus (the West Wind) spirit my sisters down to me, as he earlier wafted me down.’

She pressed seductive kisses on him, whispered honeyed words, and snuggled close to soften him. She added endearments to her charms: ‘O my honey-sweet, darling husband, light of your Psyche's life!’ Her husband unwillingly gave way before the forceful pressure of these impassioned whispers, and promised to do all she asked. Then, as dawn drew near, he vanished from his wife's embrace. As Eros had told Psyche, her sisters had indeed enquired about the location of the rock on which she had been abandoned, and they quickly made their way to it. There they cried their eyes out and beat their breasts until the rocks and crags echoed equally loudly with their repeating lamentations. Then they sought to conjure up their sister by summoning her by name, until the piercing notes of their wailing voices permeated down the mountainside, and Psyche rushed frantically and fearfully from the house. ‘Why,’ she asked, ‘do you torture yourselves to no purpose with your unhappy cries of grief? Here I am, the object of your mourning. So cease your doleful cries, and now at last dry those cheeks which are wet with prolonged tears, for you can now hug close the sister for whom you grieved.’

She then summoned Zephyrus (West Wind), and reminded him of her husband's instruction. He speedily obeyed the command, and at once whisked them down safely on the gentlest of breezes. The sisters embraced each other, and delightedly exchanged eager kisses. The tears which had been dried welled forth again, prompted by their joy. ‘Now that you are in good spirits’, said Psyche, ‘you must enter my hearth and home, and let the company of your Psyche gladden your hearts that were troubled.’

Following these words, she showed them the magnificent riches of the golden house, and let them hear the voices of her large retinue. She then allowed them the rich pleasure of a luxurious bath and an elegant meal served by her ghostly maids. But when they had had their fill of the copious abundance of riches clearly bestowed by heaven, they began to harbor deep-seated envy in their hearts. So one of them kept asking with nagging curiosity about the owner of those divine possessions, about the identity and status of her husband. Psyche in her heart's depths did not in any way disobey or disregard her husband's instructions. She invented an impromptu story that he was a handsome young man whose cheeks were just darkening with a soft beard, and who spent most of his day hunting in the hills of the countryside. But she was anxious not to betray through a slip of the tongue her silent resolve by continuing the conversation, so she weighed her sisters down with gold artifacts and precious jewels, hastily summoned Zephyrus, and entrusted them to him for the return journey. This was carried out at once, and those splendid sisters then made their way home. They were now gnawed with the bile of growing envy, and repeatedly exchanged loud-voiced complaints. One of them began: ‘Fortuna, how blind and harsh and unjust you are! Was it your pleasure that we, daughters of the same parents, should endure so different a fate? Here we are, her elder sisters, nothing better than maidservants to foreign husbands, banished from home and even from our native land, living like exiles far from our parents, while Psyche, the youngest and last offspring of our mother's weary womb, has obtained all this wealth, and a god for a husband! She has not even a notion of how to enjoy such abundant blessings. Did you notice, sister, the quantity and quality of the precious stones lying in the house, the gleaming garments, the sparkling jewels, the gold lying beneath our feet and all over the house? If she has as handsome a husband as she claims, no woman living in the whole world is more blessed. Perhaps as their intimacy continues and their love grows stronger, her God-husband will make her divine as well. That's how things are, mark my words; she was putting on such airs and graces! She's now so high and mighty, behaving like a Goddess, with those voices serving her needs, and Winds obeying her commands! Whereas my life's a hell; to begin with, I have a husband older than my father. He's balder than an onion as well, and he hasn't the virility of an infant. And he keeps our house barricaded with bards and chains.’

The other took up the grumbling. ‘I have to put up with a husband crippled and bent with rheumatism, so that he can succumb to my charms only once in a blue moon. I spent almost all my day rubbing his fingers, which are twisted and hard as flint, and burning these soft hands of mine on reeking poultices, filthy bandages, and smelly plasters. I'm a slaving nursing attendant, not a dutiful wife. You must decide for yourself, sister, how patiently or--let me express myself frankly--how menially you intent to bear the situation; I can't brook any longer the thought of this undeserving girl falling on her feet like this. Just recall how disdainfully and haughtily she treated us, how swollen-headed she'd become with her boasting and her immodest vulgar display, how she reluctantly threw at us a few trinkets from that mass of riches, and then at once ordered us to be thrown out, whisked away, sent off with the Wind because she found our presence tedious! As sure as I'm a woman, as sure as I'm standing here, I'm going to propel her headlong off that heap of riches! If the insulting way she's treated us has needled you as well, as it certainly should have, we must work out an effective plan together. We must not show the gifts in our possession to our parents or anyone else. We must not even betray the slightest awareness that she's alive. It's bad enough that we've witnessed the sorry situation ourselves, without our having to spread the glad news to our parents and the whole world at large. People aren't really fortunate if no one knows of their riches. She'll realize that she's got elder sisters, not maid-servants. So let us now go back to our husbands and homes, which may be poor but are honest. Then, when we have given the matter deeper thought, we must go back more determined to punish her arrogance.’

The two wicked sisters approved this wicked plan. So they hid away all those most valuable gifts. They tore their hair, gave their cheeks the scratching they deserved, and feigned renewed grief. Their hastily summoned tears depressed their parents, reawakening their sorrow to match that of their daughters, and then swollen with lunatic rage they rushed of to their homes, planning their wicked wiles--or rather the assassination of their innocent sister. Meanwhile, Psyche's unknown husband in their nightly conversation again counseled her with these words: ‘Are you aware what immense danger overhangs you? Tyche is aiming her darts at you from long range and, unless you take the most stringent precautions, she will soon engage with you hand to hand. Those traitorous bitches are straining every nerve to lay wicked traps for you. Above all, they are seeking to persuade you to pry into my appearance, and as I have often warned you, a single glimpse of it will be your last. So if those depraved witches turn up later, ready with their destructive designs, and I am sure they will, you must not exchange a single word with them, or at any rate if your native innocence and soft-heartedness cannot bear that, you are not to listen to or utter a single word about your husband. Soon we shall be starting a family, for this as yet tiny womb of yours is carrying for us another child like yourself. If you conceal our secret in silence, that child will be a God; but if you disclose it, he will be mortal.’

Psyche was aglow with delight at the news. She gloried in the comforting prospect of a divine child, she exulted in the fame that such a dear one would bring her, she rejoiced at the thought of the respected status of mother. She eagerly counted the mounting days and departing months, and as a novice bearing an unknown burden, she marveled that the pinprick of a moment could cause such a lovely swelling in her fecund womb.

But now those baneful, most abhorrent Furies were hastening on their impious way aboard ship, exhaling their snakelike poison. It was then that Psyche's husband on his brief visit again warned her: ‘This is the day of crisis, the moment of worst hazard. Those troublesome members of your sex, those hostile blood-relations of yours have now seized their arms, struck camp, drawn their battle-line, and sounded the trumpet-note. Your impious sisters have drawn their swords, and are aiming at your jugular. The calamities that oppress us are indeed direful, dearest Psyche. Take pity on yourself and on me; show dutiful self-control to deliver your house and your husband, your person and this tiny child of ours from the unhappy disaster that looms over us. Do not set eyes on, or open your ears to, these female criminals, whom you cannot call your sisters because of their deadly hatred, and because of the way in which they have trodden underfoot their own flesh and blood, when like Sirens they lean out over the crag, and make the rocks resound with the death-dealing cries!’

Psyche's response was muffled with tearful sobs. ‘Some time ago, I think, you had proof of my trustworthiness and discretion, and on this occasion too my resolution will likewise win your approval. Only tell our Zephyrus to provide his services again, and allow me at least a glimpse of my sisters as consolation for your unwillingness to let me gaze on your sacred face. I beg you by these locks of yours which with their scent of cinnamon dangle all round your head, by your cheeks as soft and smooth as my own, by your breast which diffuses its hidden heat, as I hope to observe your features as reflected at least in this our tiny child: accede to the devoted prayers of this careworn suppliant, and grant me the blessing of my sisters' embraces. Then you will give fresh life and joy to your Psyche, your own devoted and dedicated dear one. I no longer seek to see your face; the very darkness of the night is not oppressive to me, for you are my light to which I cling.’

Her husband was bewitched with these words and soft embraces. He wiped away her tears with his curls, promised to do her bidding, and at once departed before dawn broke.

The conspiratorial pair of sisters did not even call on their parents. At breakneck speed they made straight from the ships to the familiar rock, and without waiting for the presence of the wafting wind, launched themselves down with impudent rashness into the depths below. Zephyrus, somewhat unwillingly recalling his king's command, enfolded them in the bosom of his favoring breeze and set them down on solid earth. Without hesitation they at once marched with measured step into the house, and counterfeiting the name of sisters they embraced their prey. With joyful expressions they cloaked he deeply hidden deceit which they treasured within them, and flattered their sister with these words: ‘Psyche, you are no longer the little girl of old; you are now a mother. Just imagine what a blessing you bear in that purse of yours! What pleasures you will bring to our whole family! How lucky we are at the prospect of rearing this prince of infants! If he is as handsome as his parents--and why not?--he is sure to be a thorough Eros!’

With this pretense of affection they gradually wormed their way into their sister's heart. As soon as they had rested their feet to recover from the weariness of the journey, and had steeped their bodies in a steaming bath, Psyche served them in the dining-room with a most handsome and delightful meal of meats and savories. She ordered a lyre to play, and string-music came forth; she ordered pipes to start up, and their notes were heard; she bade choirs to sing, and they duly did. All this music soothed their spirits with the sweetest tunes as they listened, though no human person stood before them. But those baleful sisters were not softened or lulled even by that music so honey-sweet. They guided the conversation towards the deceitful snare which they had laid, and they began to enquire innocently about the status, family background, and walk of life of her husband. Then Psyche's excessive naivety made her forget her earlier version, and she concocted a fresh story. She said that her husband was a businessman from an adjoining region, and that he was middle-aged, with streaks of grey in his hair. But she did not linger a moment longer in such talk, but again loaded her sisters with rich gifts, and ushered them back to their carriage of the wind. But as they returned home, after Zephyrus with his serene breath had borne them aloft, they exchanged abusive comments about Psyche. ‘There are no words, sister, to describe the outrageous lie of that idiotic girl. Previously her husband was a young fellow whose beard was beginning to sprout with woolly growth, but now he's in middle wage with spruce and shining grey hair: What a prodigy he must be! This short interval has brought on old age abruptly, and has changed his appearance! You can be sure, sister, that this noxious female is either telling a pack of lies or does not know what her husband is like. Whatever the truth of the matter, she must be parted from those riches of hers without delay. If she does not know what her husband looks like, she must certainly be married to a god, and it is a god she's got for us in that womb of hers. Be sure of this, that if she becomes a celebrity as the mother of a divine child--which God forbid--I'll put a rope round my neck and hang myself. For the moment, then, let us go back to our parents and spin a fairy story to match the one we concocted a first.’

In this impassioned state they greeted their parents disdainfully, and after a restless night those despicable sisters sped to the rock at break of day. They threw themselves down through the air, and the Wind afforded them his usual protection. They squeezed their eyelids to force out some tears, and greeted the girl with these guileful words: ‘While you sit here, content and in happy ignorance of your grim situation, giving no thought to your danger, we in our watchful zeal for your welfare lie awake at night, racked with sadness for your misfortunes. We know for a fact--and as we share your painful plight we cannot hide it from you--that a monstrous Dragon lies unseen with you at night. It creeps along with its numerous knotted coils; its neck is blood-stained, and oozes deadly poison; its monstrous jaws lie gaping open. You must surely remember the Pythian oracle, and its chant that you were doomed to wed a wild beast. Then, too, many farms, local huntsmen, and a number of inhabitants have seen the Dragon returning to its lair at night after seeking its food, or swimming in the shallows of a river close by.

‘All of them maintain that the beast will not continue to fatten you for long by providing you with enticing food, and that as soon as your womb has filled out and your pregnancy comes to term, it will devour the richer fare which you will then offer. In view of this, you must now decide whether you ware willing to side with your sisters, who are anxious for your welfare which is so dear to their hearts, and to live in their company once you escape from death, or whether you prefer to be interred in the stomach of that fiercest of beasts. However, if you opt for the isolation of this rustic haunt inhabited only by voices, preferring the foul and hazardous intimacy of furtive love in the embrace of this venomous Dragon, at any rate we as your devoted sisters will have done our duty.’

Poor Psyche, simple and innocent as she was, at once felt apprehension at these grim tidings. She lost her head, and completely banished her recollection of all her husband's warnings and her own promises. She launched herself into the abyss of disaster. Trembling and pale as the blood drained from her face, she barely opened her mouth as she gasped and stammered out this reply to them.

‘Dearest sisters, you have acted rightly in continuing to observe your devoted duty, and as for those who make these assertions to you, I do not think that they are telling lies. It is true that I have never seen my husband's face, and I have no knowledge whatsoever of where he hails form. I merely attend at night to the words of a husband to whom I submit with no knowledge of what he is like, for he certainly shuns the light of day. Your judgment is just that he is some beast, and I rightly agree with you. He constantly and emphatically warns me against seeing what he looks like, and threatens me with great disaster if I show curiosity about his features. So if at this moment you can offer saving help to your sister in her hour of danger, you must come to my rescue now. Otherwise your indifference to the future will tarnish the benefits of your previous concern.’

Those female criminals had now made their way through the open gates, and had occupied the mind of their sister thus exposed. They emerged from beneath the mantel of their battering-ram, drew their swords, and advanced on the terrified thoughts of that simple girl. So it was that one of them said to her: ‘Our family ties compel us, in the interests of your safety, to disregard any danger whatsoever which lies before us, so we shall inform you of the one way by which you will attain the safety which has exercised us for so long. You must whet a razor by running it over your softened palm, and when it is quite sharp hide it secretly by the bed where you usually lie. Then fill a well-trimmed lamp with oil, and when it is shining brightly, conceal it beneath the cover of an enclosing jar. Once you have purposefully secreted this equipment, you must wait until your husband ploughs his furrow, and enters and climbs as usual into bed. Then, when he has stretched out and sleep has begun to oppress and enfold him, as soon as he starts the steady breathing which denotes deep sleep, you must slip off the couch. In your bare feet and on tiptoe take mincing steps forward, and remove the lamp from its protective cover of darkness. Then take your cue from the lamp, and seize the moment to perform your own shining deed. Grasp the two-edged weapon boldly, first raise high your right hand, and then with all the force you can muster sever the knot which joins the neck and head of that venomous serpent. You will not act without our help, for we shall be hovering anxiously in attendance, and as soon as you have ensured your safety by his death, we shall fly to your side. All these riches here we shall bear off with you with all speed, and then we shall arrange an enviable marriage for you, human being with human being.’ Their sister was already quite feverish with agitation, but these fiery words set her heart ablaze. At once they left her, for their proximity to this most wicked crime made them fear greatly for themselves. So the customary thrust of the winged Breeze bore them up to the rock, and they at once fled in precipitate haste. Without delay they embarked on their ships and cast off.

But Psyche, now left alone, except that being harried by the hostile Furies was no solitude, tossed in her grief like the waves of the sea. Though her plan was formed and her determination fixed, she still faltered in uncertainty of purpose as she set her hands to action, and was torn between the many impulses of her unhappy plight. She made haste, she temporized; her daring turned more to fear, her diffidence to anger, and to cap everything she loathed the beast but loved the husband, though they were one and the same. But now evening brought on darkness, so with headlong haste she prepared the instruments for the heinous crime. Night fell, and her husband arrived, and having first skirmished in the warfare of love, he fell in to a heavy sleep.

Psyche views Eros

Psyche, though enfeebled in both body and mind, gained the strength lent her by fate's harsh decree. She uncovered the lamp, seized the razor, and showed a boldness that belied her sex. But as soon as the lamp was brought near, and the secrets of the couch were revealed, she beheld of all beasts the gentlest and sweetest, Eros himself, a handsome god lying in a handsome posture. Even the lamplight was cheered and brightened on sighting him, and the razor felt suitable abashed at its sacrilegious sharpness. As for Psyche, she was awe-struck at this wonderful vision, and she lost all her self-control. She swooned and paled with enervation; her knees buckled, and she sought to hide the steel by plunging it into her own breast. Indeed, she would have perpetrated this, but the steel showed its fear of committing so serious a crime by plunging out of her rash grasp. But as in her weariness and giddiness she gazed repeatedly on the beauty of that divine countenance, her mental balance was restored. She beheld on his golden head his luxuriant hair steeped in ambrosia; his neatly pinned ringlets strayed over his milk-white neck and rosy cheeks, some dangling in front and some behind, and their surpassing sheen made even the lamplight flicker. On the winged God's shoulders his dewy wings gleamed white with flashing brilliance; though they lay motionless, the soft and fragile feathers at their tips fluttered in quivering motion and sported restlessly. The rest of his body, hairless and rosy, and was such that Aphrodite would not have been ashamed to acknowledge him as her son. At the foot of the bed lay his bow, quiver, and arrows, the kindly weapons of that great God.

As Psyche trained her gaze insatiably and with no little curiosity on these her husband's weapons, in the course of handling and admiring them she drew out an arrow from the quiver, and tested its point on the tip of her thumb. But because her arm was still trembling she pressed too hard, with the result that it pricked too deeply, and tiny drops of rose-red blood bedewed the surface of the skin. So all unknowing and without prompting Psyche fell in love with Eros, being fired more and more with desire for the god of desire. She gazed down on him in distraction, and as she passionately smothered him with wanton kisses from parted lips, she feared that he might stir in his sleep. But while her wounded heart pounded on being roused by such striking beauty, the lamp disgorged a drop of burning oil from the tip of its flame upon the god's right shoulder; it could have been nefarious treachery, or malicious jealousy, or the desire, so to say, to touch and kiss that glorious body.

O you rash, reckless lamp, Amor's (Love's) worthless servant, do you burn the very god who possesses all fire, though doubtless you were invented by some lover to ensure that he might possess for longer and even at night the object of his desire? The god started up on being burnt; he saw that he was exposed, and that his trust was defiled. Without a word he at once flew away from the kisses and embrace of his most unhappy wife.

But Psyche seized his right leg with both hands just as he rose above her. She made a pitiable appendage as he soured aloft, following in his wake and dangling in company with him as they flew through the clouds. But finally she slipped down to earth exhausted. As she lay there on the ground, her divine lover did not leave her, but flew to the nearest cypress-tree, and from its summit spoke in considerable indignation to her.

‘Poor, ingenuous Psyche, I disregarded my mother Aphrodite's instructions when she commanded that you be yoked in passionate desire to the meanest of men, and that you be then subjected to the most degrading of marriages. Instead, I preferred to swoop down to become your lover. I admit that my behavior was not judicious; I, the famed archer, wounded myself with my own weapon, and made you my wife--and all so that you should regard me as a wild beast, and cut off my head with the steel, and with it the eyes that dote on you! I urged you repeatedly, I warned you devotedly always to be on your guard against what has now happened. But before long those fine counselors of yours will make satisfaction to me for their heinous instructions, whereas for you the punishment will be merely my departure.’ As Eros flew away he added "love cannot exist without trust."

Then Psyche fell flat on the ground, and as long as she might see her husband, she cast her eyes after him into the air, weeping and lamenting piteously; but when he was gone out of her sight, she threw herself into the next running river, for the great anguish and dolour that she was in, for the lack of her husband. Howbeit the water would not suffer her to be drowned, but took pity upon her, in the honour of Eros which accustomed to broil and burn the river, and so threw her upon the bank amongst the herbs.

Pan & Psyche

Then Pan, the rustical God, sitting on the riverside, embracing and teaching the Goddess Canna to tune her songs and pipes, by whom were feeding the young and tender goats, after that he perceived Psyche in so sorrowful case, not ignorant, I know not by what means, of her miserable estate, endeavoured to pacify her in this sort: "O fair maid, I am a rustic and rude herdsman, howbeit, by reason of my old age, expert in many things; for as far as I can learn by conjecture, which, according as wise men do term, is called divination, I perceive by your uncertain gait, your pale hue, your sobbing sighs, and your watery eyes, that you are greatly in love. Wherefore hearken to me, and go not about to slay yourself, nor weep not at all, but rather adore and worship the great God Eros, and win him unto you by your gentle promise of service." When the God of Shepherds had spoken these words, she gave no answer but made reverence unto him as to a God, and so departed.

After that Psyche had gone a little way, she fortuned unawares to come to a city where the husband of one of her sisters did dwell; which when Psyche did understand, she caused that her sister had knowledge of her coming, and so they met together, and after great embracing and salutation, the sister of Psyche demanded the cause of her travel thither. "Marry," quoth she, "do not you remember the counsel that you gave me, whereby you would that I should kill the beast, who under colour of my husband did lie with me every night? You shall understand, that as soon as I brought forth the lamp to see and behold his shape, I perceived that he was the son of Aphrodite, even Eros himself that lay with me. Then I, being stroken with great pleasure, and desirous to embrace him, could not thoroughly assuage my delight, but alas! by evil chance, the boiling oil of the lamp fortuned to fall on his shoulder, which caused him to awake, who, seeing me armed with fire and weapon, began say: 'How darest thou be so bold as to do so great a mischief? Depart from me, and take such things as thou didst bring: for I will have thy sister (and named you) to my wife, and she shall be placed in my felicity.' And by and by he commanded Zephyrus to carry me away from the bounds of his house."

Psyche had not yet finished speaking when her sister, goaded by mad lust and destructive envy, swung into action. She devised a lying excuse to deceive her husband, pretending that she had learnt of her parents' death; she at once boarded ship, and then made hot-foot for the rock. Although the wrong wind was blowing, her eagerness was fired by blind hope, and she said: ‘Take me, Eros, as your worthy wife; Zephyrus, take your mistress aboard!’ She then took a prodigious leap downward. But not even in death could she reach that abode for her limbs bounced on the rocky crags, and were fragmented. Her insides were torn out, and in her fitting death she offered a ready meal to birds and beasts. The second punitive vengeance was not long delayed. Psyche resumed her wandering, and reached a second city where her other sister similarly dwelt. She too was taken in by her sister's deception, and in her eagerness to supplant Psyche in the marriage which they had befouled, she hastened to the rock, and fell to her deadly doom in the same way.

Meanwhile, Eros had flown to his mother's palace to get his wound tended to, Aphrodite who was bathing in the ocean received word from a seagull that Eros had been wounded and his life was in danger and there were rumors that it was thanks to a woman whom Eros had been with for quite some time.

Upon hearing the news that her son had been wounded Aphrodite was filled with rage and asked the bird "Who is it who has tempted my innocent, beardless boy? Is it one of that crowd of Nymph, or one of the Horae (Seasons), or one of the band of The Muses, or one of my servant Gratiae (Graces)?’ The garrulous bird did not withhold a reply. She said: ‘I do not know, mistress; I think the story goes that he is head over heels in love with a girl by the name of Psyche, if my memory serves me rightly.’ Upon hearing this Aphrodite's feelings of anger towards whoever hurt her son and pity towards her son were quickly changed to feelings of anger and betrayal of her son and fury that Psyche had not only not fallen in love with a beast but had also wounded her Eros. Aphrodite told Eros ‘This is a fine state of affairs, just what one would expect from a child of mine, from a decent man like you! First of all you trampled underfoot the instructions of your mother--or I should say your employer--and you refused to humble my personal enemy with a vile love-liaison; and then, mark you, a mere boy of tender years, you hugged her close in your wanton, stunted embraces! You wanted me to have to cope with my enemy as a daughter-in-law! You take too much for granted, you good-for-nothing, loathsome seducer! You think of yourself as my only noble heir, and you imagine that I'm now too old to bear another. Just realize that I'll get another son, one far better than you. In fact I'll rub your nose in it further. I'll adopt one of my young slaves, and make him a present of these wings and torches of yours, the bow & arrows, and all the rest of my paraphernalia which I did not entrust to you to be misused like this. None of the cost of kitting you out came from your father's estate." The goddess then sought to find Psyche to punish her.

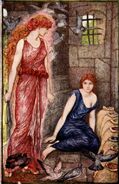

Immediately as she was going away, came Hera and Demeter demanding the cause of her anger. Then Aphrodite made answer: "Verily you are come to comfort my sorrow, but I pray you with all diligence to seek out one whose name is Psyche, who is a vagabond and runneth about the countries, and as I think, you are not ignorant of the bruit of my son Eros, and of his demeanour, which I am ashamed to declare." Then they understanding and knowing the whole matter, endeavoured to mitigate the ire of Aphrodite in this sort.

"What is the cause, madame, or how hath your son so offended, that you should so greatly accuse his love, and blame him by reason that he is amorous? and why should you seek the death of her, whom he doth fancy? We most humbly entreat you to pardon his fault, if he have accorded to the mind of any maiden. What, do not you know that he is a young man? or have you forgotten of what years he is? doth he seem always to you to be a child? You are his mother, and a kind woman, will you continually search out his dalliance? Will you blame his luxury? Will you bridle his love, and will you reprehend your own art and delights in him? What God or man is he, that can endure that you should sow or disperse your seed of love in every place, and to make a restraint thereof within your own doors? Certes, you will be the cause of the suppression of the public places of young dames."

In this sort these Goddesses endeavoured to pacify her mind, and to excuse Eros with all their power, although he were absent, for fear of his darts and shafts of love. But Aphrodite would in no wise assuage her heat; but thinking that they did but trifle and taunt at her injuries, she departed from them, and took her voyage towards the sea in all haste. Psyche however was spending her time searching far and wide for her lover fruitlessly praying to every deity hoping one would answer her. finally stumbling into a temple where everything is in slovenly disarray. She saw ears of wheat in a heap, and others woven into a garland, and ears of barley as well. There were sickles lying there, and a whole array of harvesting implements, but they were in a jumbled and neglected heap, thrown carelessly by workmen's hands, as happens in summer-time. Psyche carefully sorted them out and ordered them in separate piles; no doubt she reflected that she should not neglect the shrines and rites of any deity.

Kindly Demeter sighted her as she carefully and diligently ordered these offerings, and at once she cried out from afar: ‘Why, you poor Psyche! Aphrodite is in a rage, mounting a feverish search for your traces all over the globe. She has marked you down for the sternest punishment, and is using all the resources of her divinity to demand vengeance. And here you are, looking to my interests, with your mind intent on anything but your own safety!’

Then Psyche groveled at the goddess's feet, and watered them with a stream of tears. She swept the ground with her hair, and begged Demeter's favor with a litany of prayers. ‘By your fruitful right hand, by the harvest ceremonies which assure plenty, by the silent mysteries of your baskets and the winged courses of your attendant Dracones, by the furrows in your Sicilian soil, by Persephone's descent to a lightless marriage, and by your daughter's return to rediscovered light, and by all else which the shrine of Attic Eleusis shrouds in silence--I beg you, lend aid to this soul of Psykhe which is deserving of pity, and now entreats you. Allow me to lurk hidden here among these heaps of grain if only for a few days, until the great goddess's raging fury softens with the passage of time, or at any rate till my strength, which is now exhausted by protracted toil, is assuaged by a period of rest.’

Demeter answered her: ‘Your tearful entreaties certainly affect me and I am keen to help you, but I cannot incur Aphrodite's displeasure, for I maintain long-standing ties of friendship with her--and besides being my relative, she is also a fine woman. So you must quit this dwelling at once, and count it a blessing that I have not turned you over to Aphrodide.'

Then Psyche driven away contrary to her hope, was double afflicted with sorrow, and so she returned back again. And behold, she perceived afar off in a valley a temple standing within a forest, fair and curiously wrought; and minding to overpass no place, whither better hope did direct her, and to the intent she would desire the pardon of every God, she approached nigh to the sacred doors, whereas she saw precious riches and vestments engraven with letters of gold, hanging upon branches of trees, and the posts of the temple, testifying the name of the Goddess Hera to whom they were dedicated. Then she kneeled down upon her knees, and embracing the altar with her hands, and wiping her tears, gan pray in this sort. "O dear spouse and sister of the great God Zeus, which art adored and worshipped among the great temples of Samos, called upon by women with child, worshipped at high Carthage, because thou werest brought from heaven by the Lion, the rivers of the flood Inachus do celebrate thee, and know that thou art the wife of the great God and the Goddess of Goddesses. All the East part of the world hath thee in veneration, all the world calleth thee Lucina: I pray thee to be mine advocate in my tribulations, deliver me from the great danger which pursueth me, and save me that am wearied with so long labours and sorrow, for I know that it is thou that succourest and helpest such women as are with child and in danger."

Then Hera, hearing the prayers of Psyche, appeared unto her in all her royalty, saying: "Certes, Psyche, I would gladly help thee, but I am ashamed to do anything contrary to the will of my daughter-in-law Aphrodite, whom always I have loved as mine own child; moreover I shall incur the danger of the law intituled De servo corrupto, whereby I am forbidden to retain any servant fugitive against the will of his master."

With all hope gone Psyche pondered seeking out the goddess of love herself in the hopes of minimalizing the goddess' anger. Soon after Psyche learned that Aphrodite who was seeking Psyche had offered a reward of 'seven sweet kisses, and a particularly honeyed one imparted with the thrust of her caressing tongue.’ Believing she had nothing to lose Psyche set off to find the goddess of love thinking to herself "who knows, if he is not at his mother's house.

Psyche approached the abode of Aphrodite where a member of Aphrodite's household called Consueto (Habit) confronted her, and at once cried out at the top of her voice: ‘Most wicked of all servants, have you at last begun to realize that you have a mistress? Or are you, in keeping with the general run of your insolent behavior, still pretending to be unaware of the exhausting efforts we have endured in searching for you? How appropriate it is that you have fallen into my hands rather than anyone else's. You are now caught fast in the claws of Hades, and believe me, you will suffer the penalty for your gross impudence without delay.

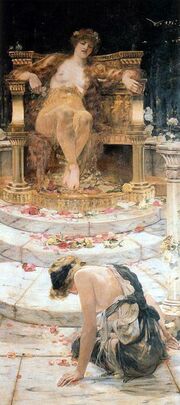

Psyche was brought before Aphrodite who seeing her uttered the sort of explosive cackle typical of people in a furious rage. She wagged her head, scratched her right ear, and said: ‘Oh, so you have finally condescended to greet your mother-in-law, have you? Or is the purpose of this visit rather to see your husband, whose life is in danger from the wound which you inflicted? You can rest assured that I shall welcome you as a good mother-in-law should.’ Then she added : ‘Where are my maids Sollicito (Melancholy) and Tristie (Sorrow)?’ They were called in, and the goddess consigned Psyche to them for tortured and whipped. They obeyed their mistress's instruction, laid into poor Psyche and tortured her with other implements, and then restored her to their mistress's presence.

Psyche is whipped by Aphrodite's hamndmaidens.

Upon seeing Psyche again and noticing that Psyche was with child Aphrodite renewed her laughter. ‘Just look at her,’ she taunted ‘With that appealing swelling in her belly, she makes me feel quite sorry for her. I suppose she intends to make me a happy grandmother of that famed offspring; how lucky I am, in the bloom of my young days, at the prospect of being hailed as a grandma, and having the son of a cheap maidservant called Aphrodite's grandson! But what a fool I am, mistakenly calling him a son, for the wedding was not between a couple of equal status. Besides, it took place in a country house, without witnesses and without a father's consent, so it cannot be pronounced legal. The child will therefore be born a bastard--if we allow you to reach full term with him at all!’ Saying this, she flew at Psyche, ripped her dress to shreds, tore her hair, made her brains rattle by pounding Psyche's head on the ground, and pummeled her severely.

After the brutal attack was over Aphrodite told Psyche "you are such a plain and ill-favored a girl you will never be able to get a husband except by the most diligent and painful service. I will therefore show you my good will by training you, I will make you my slave."

Aphrodite then brought some wheat, barley, millet, poppy seed, chickpeas, lentils and beans. She mingled them together in an indiscriminate heap, and said to her: ‘You are such an ugly maidservant that I think the only way you win your lovers is by devoted attendance, so I'll see myself how good you are. Separate out this mixed heap of seeds, and arrange the different kinds in their proper piles. Finish the work before tonight, and show it to me to my satisfaction.’ following with the ominous words "for your own sake." Having set before her this enormous pile of seeds, Aphrodite went off to a wedding-dinner.

Psyche did not lay a finger on this confused heap, which was impossible to separate. She was dismayed by this massive task imposed on her, and stood in stupefied silence. Then miraculously in her most dire moment Psyche who had awakened no compassion in mortals or immortals was aided by the smallest of creatures when a little country-ant got wind of her great problem. It took pity on the great God's consort, and cursed the vindictive behavior of Aphrodite. Then it scurried about, energetically summoning and assembling a whole army of resident ants: ‘have pity, noble protégées of Gaea (Earth), our universal mother; have pity, and with eager haste lend your aid to this refined girl, who is Amor's (Eros) wife.’ Wave after wave of the tribe of ants swept in; with the utmost enthusiasm each and all divided out the heap grain by grain, and when they had sorted them into their different kinds, they swiftly vanished from sight. That evening As night fell, Aphrodite returned from the wedding-feast flushed with wine and perfumed with balsam, her whole body wreathed with glowing roses. When she observed the astonishing care with which the task had been executed, she said: ‘This is not your work, you foul creature; the hands that accomplished it are not yours, but his whose favor you gained, though little good it's done you, or him either!’ The goddess threw her a crust of hard black bread warning her "your work is by no means over" and left Psyche to sleep on the ground while the goddess herself went off to sleep on her soft fragrant bed. Aphrodite went to bed that night pleased left pleased thinking about how if she could keep Psyche half-starved and at hard labor, that combined with Psyche's pregnancy would surely take Psyche's beauty away. Aphrodite was also pleased knowing Eros was alone, closely guarded and confined in a single room at the back of the house. This was partly to ensure that he did not aggravate his wound by wanton misbehavior, and partly so that he would not meet his dear one. So the lovers though under the one roof were kept apart from each other, and were made to endure a wretched night.

The next morning as soon as Eos's Dawn's chariot appeared, Aphrodite who had devised a new task (this time dangerous) summoned Psyche, and spoke to her like this: ‘Do you see the grove there, flanked by the river which flows by it, its banks extending into the distance and its low-lying bushes abutting on the stream? There are sheep in it wandering and grazing unguarded, and their fleeces sprout with the glory of pure gold, I order you to go there at once, and somehow or other obtain and bring back to me a tuft of wool from the precious fleece.’

As Psyche began to cross something inside Psyche longed to throw herself into the river and end her suffering however from that stretch of stream one of the green reeds which foster sweet music was divinely inspired by the gentle sound of a caressing breeze, and uttered this prophecy: ‘Psyche, even though you are harrowed by great trials, do not pollute my waters by a most wretched death. You must not approach the fearsome sheep at this hour of the day, when they tend to be fired by the burning heat of the sun and charge about in ferocious rage; with their sharp horns, their rock-hard heads, and sometimes their poisonous bites, they wreak savage destruction on human folk. But one the hours past noon have quelled the sun's heat, and the flocks have quieted down under the calming influence of the river-breeze, you will be able to approach while they are napping and you will find golden wool clinging to the sharp briar of the bushes there you will be able to find an ample amount to bring to your mistress." Psyche obeyed every detail, and the theft was easily accomplished. She gathered the soft substance of yellow gold in her dress, and that evening brought back the wool to Aphrodite.

The success of the second task had in no way won her favorable acknowledgement from her mistress at least, for Aphrodite who believed that Eros had somehow had a hand in Psyche's success with the tasks frowned heavily, smiled harshly, and said: ‘I know quite well that this too is the work of that son of mine. But no I shall try you out in earnest, to see if you are indeed endowed with brave spirit and unique circumspection. Do you see that lofty mountain-peak, perched above a dizzily high cliff, from where the livid waters of a dark spring come tumbling down, and when enclosed in the basin of he neighboring valley, water the marshes of the River Styx (the river of hatred) and feed the hoarse streams of the River Cocytus (the river of lamentation)? I want you to hurry and bring me back in this small jug some icy water drawn from the stream's highest point, where it gushes out from within.’ Handing Psyche a vessel shaped from crystal, she backed this instruction with still harsher threats.

Psyche made for the topmost peak with swift and eager step, The moment she neared the vicinity of the specified mountain-range, she became aware of the lethal difficulty posed by her daunting task. A rock of huge size towered above her, hard to negotiate and treacherous because of its rugged and slippery surface. From its stony jaws it belched forth repulsive waters which issued directly from a vertical cleft. The stream glided downward, and being concealed in the course of the narrow channel which it had carved out, it made its hidden way into a neighboring valley. From the hollow rocks on the right and left fierce snakes crept out, extending their long necks, their eyes unblinkingly watchful and maintaining unceasing vigil. The waters themselves formed an additional defense, for as they came from the river known for lamentation they had the power of speech, and from time to time would cry out ‘Clear off!’ or ‘Watch what you're doing!’, or ‘What's your game? Lookout!’, or ‘Cut and run!’, or ‘you won't make it!’ The hopelessness of the situation turned Psyche to stone. She was physically present, but her senses deserted her. She was utterly downcast by the weight of inescapable danger; she could not even summon the ultimate consolation of tears. But the privations of this innocent soul did not escape the steady gaze of benevolent Providentia (Providence). Suddenly highest Zeus' royal bird appeared with both wings outstretched: this is the eagle, the bird of prey who recalled his service of long ago, when following Eros' guidance he had borne the Phrygian cupbearer Ganymede to Zeus. The bird now lent timely aid, and directed his veneration for Eros's power to aid his wife in her ordeal. He quitted the shining paths of high heaven, flew down before the girl's gaze, and broke into speech : ‘You are in all respects an ingenuous soul without experience in things such as this, so how can you hope to be able to steal the merest drop from this most sacred and unfriendly stream, or even apply your hand to it? Rumor at any rate, as you know, has it that these Stygian waters are an object of fear to the gods and to Zeus himself, that just as you mortals swear by the gods' divine power, so those gods frequently swear by the majesty of the River Styx. So here, hand me that jug of yours.’ At once he grabbed it, and hastened to fill it with water. Balancing the weight of his drooping wings, he used them as oars on right and left to steer a course between the serpents' jaws with their menacing teeth and the triple-forked darting of their tongues. He gathered some water in the face of its reluctance and its warning to him to depart before he suffered harm; he falsely claimed the Aphrodite had ordered him to collect it, and that he was acting in her service, which made it a little easier for him to approach. So, Psyche joyously took the filled jug and hastened to return it to Aphrodite who upon seeing Psyche's success had readied another task even more dangerous.

The 3rd Task

Aphrodite, furious at Psyche's survival flashed a menacing smile as she addressed her with threats of yet more monstrous ill-treatment: ‘Now indeed I regard you as a witch with great and lofty powers, for you have carried out so efficiently commands of mine such as these. I have yet conceived yet another task." Aphrodite claimed that the stress of caring for her son, made depressed and ill as a result of Psyche's lack of faith, has caused her to lose some of her beauty. Psyche was ordered to go to the Underworld and tell the Persephone, Queen of the Underworld "Aphrodite asks you to send her a small supply of your beauty-preparation, enough for just one day, because she has been tending her sick son, and has used hers all up by rubbing it on him." Make your way back with it as early as you can, because I need it to doll myself up so as to attend the Deities' Theatre.’

Psyche believing this final task to be impossible saw clearly that she was being driven to her immediate doom. It could not be otherwise, for she was being forced to journey on foot of her own accord to Hades and the shades below. She lingered no longer, but made for a very high tower, intending to throw herself headlong from it, for she thought that this was the direct and most glorious route down to the world below. But the tower suddenly burst into speech, and said: ‘Poor girl, why do you seek to put an end to yourself by throwing yourself down? What is the point of rash surrender before this, your final hazardous labor? Once your spirit is sundered from your body, you will certainly descent to the depths of Hades without the possibility of a return journey.

Psyche in Charon's boat

‘Listen to me. Sparta, the famed Achaean city, lies not far from here. On its borders you must look for Taenarus, which lies hidden in a trackless region. Hades has his breathing-vent there, and a sign-post points through open gates to the track which none should tread. Once you have crossed the threshold and committed yourself to that path, the track will lead you directly to Orcus' very palace. But you are not to advance through that dark region altogether empty-handed, but carry in both hands barley-cakes baked in sweet wine, and have between your lips twin coins. When you are well advanced on your infernal journey, you will meet a lame ass carrying a load of logs, with a driver likewise lame; he will ask you to hand him some sticks which have slipped from his load, but you must pass in silence without uttering a word. Immediately after that you will reach the lifeless River Akheron (the river of woe) over which Charon presides. He peremptorily demands the fare, and when he receives it he transports travelers on his stitched-up craft over to the further shore. (So even among the dead, greed enjoys its life; even that great God Charon, who gathers taxes for Hades does not do anything for nothing. A poor man on the point of death must find his fare, and no one will let him breathe his last until he has his copper ready.) You must allow this squalid elder to take for your fare one of the coins you are to carry, but he must remove it from your mouth with his own hand. Then again, as you cross the sluggish stream, and old man now dead will float up to you, and raising his decaying hands will beg you to drag him into the boat; but you must not be moved by a sense of pity, for that is not permitted. ‘When you have crossed the river and have advanced a little further, some aged women weaving at the loom will beg you to lend a hand for a short time. But you are not permitted to touch that either, for all these and many other distractions are part of the ambush which Aphrodite will set to induce you to release one of the cakes from your hands. Do not imaging that the loss of a mere barley cake is a trivial matter, for if you relinquish either of them, the daylight of this world above will be totally denied you. Posted there is Cerberus, massive hound with a huge, triple-formed head. This monstrous, fearsome brute confronts the dead with thunderous barking, though his menaces are futile since he can do them no harm. He keeps constant guard before the very threshold and the dark hall of Persephone, protecting that deserted abode of Hades. You must disarm him by offering him a cake as his spoils. Then you can easily pass him, and gain immediate access to Persephone herself. She will welcome you in genial and kindly fashion, and she will try to induce you to sit on a cushioned seat beside her and enjoy a rich repast. But you must settle on the ground, ask for course bread, and eat it. Then you must tell her why you have come. When you have obtained what she gives you, you must make your way back, using the remaining cake to neutralize the dog's savagery. Then you must give the greedy mariner the one coin which you have held back, and once again across the river you must retrace your earlier steps and return to the harmony of heaven's stars. Of all these injunctions I urge you particularly to observe this: do not seek to open or to pry into the box that you will carry, nor be in any way inquisitive about the treasure of divine beauty hidden within it.’

This was how that far-sighted tower performed its prophetic role. Psyche immediately sped to Taenarus, and having duly obtained the coins and cakes she hastened down the path to Hades. She passed the lame ass-driver without a word, handed the fare to the ferryman for the river crossing, ignored the entreaty of the dead man floating on the surface, disregarded the crafty pleas of the weavers, fed the cake to the dog to quell his fearsome rage, and gained access to the house of Persephone. Psyche declined the soft cushion and the rich food offered by her hostess; she perched on the ground at her feet, and was content with plain bread. She then reported her mission from Aphrodite. The box was at once filled and closed out of her sight, and Psyche took it. She quieted the dog's barking by disarming it with the second cake, offered her remaining coin to the ferryman, and quite animatedly hastened out of Hades. But once she was back in the light of this world and had reverently hailed it, her mind was dominated by rash curiosity which continued to nag at her as she drew close to Aphrodite' palace, in spite of her eagerness to see the end of her service. She said: ‘How stupid I am to be carrying this beauty-lotion fit for deities, and not take a single drop of it for myself, for with this at any rate I can be pleasing to my beautiful lover.’

The words were scarcely out of her mouth when she opened the box. But inside there was no beauty-lotion or anything other than the sleep of Hades, a truly Stygian sleep. As soon as the lid was removed and it was laid bare, it attacked her and pervaded all her limbs in a thick cloud. It laid hold of her, so that she fell prostrate on the path where she had stood. She lay there motionless, no more animate than a corpse at rest.

But Eros was now recovering, for his wound had healed. He could no longer bear Psyche's long separation from him, and since the door to his room was locked he glided out of the high-set window of the chamber which was his prison. His wings were refreshed after their period of rest, so he progressed much more swiftly to reach his Psyche. Carefully wiping the sleep from her, he restored it to its former lodging in the box. Then he roused Psyche with an innocuous prick of his arrow. ‘Poor, dear Psyche,’ he exclaimed, ‘see how as before your curiosity might have been your undoing! But now hurry to complete the task imposed on you by my mother's command; I shall see to the rest.’

After saying this, her lover rose lightly on his wings, while Psyche hurried to bear Persephone's gift back to Aphrodite.

Meanwhile, Eros, devoured by overpowering desire and with lovelorn face, feared the sudden arrival of his mother's sobering presence, so he reverted to his former role and rose to heaven's peak on swift wings. With a suppliant posture he laid his case before the great Zeus, who took Eros' little cheek between his finger and thumb, raised the boy's hand to his lips and kissed it, and then said to him: ‘honored son, you have never shown me the deference granted me by the gods' decree. You keep piercing this heart of mine, which regulates the elements and orders the changing motion of the stars, with countless wounds. You have blackened it with repeated impulses of earthly lust, damaging my prestige and reputation by involving me in despicable adulteries which contravene the laws--the lex Julia itself--and public order. You have transformed my smiling countenance into grisly shapes of snakes, fires, beasts, birds, and cattle. Yet in spite of all this, I shall observe my usual moderation, recalling that you were reared in these arms of mine. So I will comply with all that you ask, as long as you know how to cope with your rivals in love; and if at this moment there is on earth any girl of outstanding beauty, as long as you can recompense me with her.’

After saying this, he ordered Hermes to summon all the gods at once to an assembly, and to declare that any absentee from the convocation of heavenly citizens would be liable to a fine of ten thousand sesterces. The theatre of heaven at once filled up through fear of this sanction. Towering Zeus, seated on his lofty throne, made his proclamation: ‘You gods whose names are inscribed on the register of the Muses, you all surely know this young fellow who was reared by my own hands. I have decided that the hot-headed impulses of his early youth need to be reined in; he has been the subject of enough notoriety in day-to-day gossip on account of his adulteries and all manner of improprieties. We must deprive him of all opportunities; his juvenile behavior must be shackled with the chains of marriage. He has chosen the girl, and robbed her of her virginity, so he must have and hold her. Let him take Psyche in his embrace and enjoy his dear one ever after.’

Then he turned to address Aphrodite. ‘My daughter’, he said, ‘do not harbor any resentment. Have no fear for you high lineage and distinction in this marriage to a mortal, for I shall declare the union lawful and in keeping with the civil law, and not one between persons of differing social status. There and then he ordered that Psyche be detained and brought up to heaven through Hermes's agency. He gave her a cup of ambrosia, and said : ‘Take this, Psyche, and become immortal. Eros will never part from your embrace; this marriage of yours shall be eternal.’

At once a lavish wedding-feast was laid. The bridegroom reclined on a couch of honor, with Psyche in his lap. Zeus likewise was paired with Hera, and all the other deities sat in order of precedence. Then a cup of nectar, the gods' wine, was served to Zeus by his cup-bearer Ganymede, that well-known country-lad, and to the others by Dionysius. Hephaestus cooked the dinner, the Horae (Seasons) brightened the scene with roses and other flowers, the Graiae (Graces) diffused balsam, and the Muses, also present, sang in harmony. Apollo sang to the lyre, and Aphrodite grudgingly took to the floor to the strains of sweet music, and danced prettily. She had organized the performance so that the Muses sang in chorus, a Satyrs played the flute, and a Pan sang to the shepherd's pipes. This was how with due ceremony Psyche was wed to Eros despite his mother's displeasure (Aphrodite raging about it for weeks).

However, not long after, at full term a daughter was born to them. We call her Hedone (Pleasure/Bliss). Aphrodite reflected that with living in Olympus with a husband and a daughter to care for would not attract the attention of men and interfere with her own worship. Thus Aphrodite reconciled with Psyche and all came together love (Eros) and soul (for that is what Psyche means).